Ballyvolane, Mardyke, Ballyphehane, Dunkettle, Ballincrokig, Sunday's Well, Knocknaheeney, Commons, The Lough, Gurranabraher, Garranedarragh, Glasheen, Knocknacullen East, Ballinlough, Lehenagh More, Poulacurry South, Mayfield, Ballintemple, Ballincolly, Knocknacullen West

Shandon, Ballyphehane, Montenotte, Blackrock, Douglas, Centre, Knocknaheeney, Ballintemple, Victorian Quarter, Blackpool, Grange, Mahon, Sunday's Well, Knockglass, Duneen, Courtaparteen, Castlehaven, Derry

|

Coláiste na hOllscoile, Corcaigh

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

| Latin: Universitas Hiberniae Nationali apud Corcagium | ||||||||

|

Former name

|

Queen's College, Cork | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motto | Where Finbarr Taught Let Munster Learn | |||||||

| Established | 1845; 177 years ago | |||||||

| Founder | Queen Victoria[1] | |||||||

| President | John O'Halloran[2] | |||||||

|

Academic staff

|

762 (2010)[3] | |||||||

| Undergraduates | c.15,000 (2016)[4] | |||||||

| Postgraduates | c.4,400 (2016)[4] | |||||||

| Address |

College Road

,

,

51.893°N 8.493°WCoordinates: 51.893°N 8.493°WCoordinates:  51.893°N 8.493°W 51.893°N 8.493°W |

|||||||

| Colours |

|

|||||||

| Affiliations | AUA EUA NUI IUA UI Utrecht Network |

|||||||

| Website | www |

|||||||

University College Cork – National University of Ireland, Cork (UCC)[5] (Irish: Coláiste na hOllscoile Corcaigh) is a constituent university of the National University of Ireland, and located in Cork.

The university was founded in 1845 as one of three Queen's Colleges located in Belfast, Cork, and Galway.[6] It became University College, Cork, under the Irish Universities Act of 1908. The Universities Act 1997 renamed the university as National University of Ireland, Cork, and a Ministerial Order of 1998 renamed the university as University College Cork – National University of Ireland, Cork,[7] though it continues to be almost universally known as University College Cork.

Amongst other rankings and awards, the university was named Irish University of the Year by The Sunday Times on five occasions; most recently in 2017.[8][9] In 2015, UCC was also named as top performing university by the European Commission funded U-Multirank system, based on obtaining the highest number of "A" scores (21 out of 28 metrics) among a field of 1200 partaking universities.[10] UCC also became the first university to achieve the ISO 50001 standard in energy management in 2011.

Queen's College, Cork, was founded by the provisions of an act which enabled Queen Victoria to endow new colleges for the "Advancement of Learning in Ireland". Under the powers of this act, the three colleges of Belfast, Cork and Galway were incorporated on 30 December 1845. The college opened in 1849 with 23 professors and 181 students; Medicine, Arts, and Law were the three founding faculties. A year later the college became part of the Queen's University of Ireland.

The original site chosen for the college was considered appropriate as it was believed to have had a connection with the patron saint of Cork, Saint Finbarr. His monastery and school of learning were close by at Gill Abbey Rock and the mill attached to the monastery is thought to have stood on the bank of the south channel of the River Lee, which runs through the college lower grounds. This association is also reflected in the college motto "Where Finbarr Taught, Let Munster Learn" which is also the university motto.

Adjacent to Gillabbey and overlooking the valley of the river Lee, the site was selected in 1846.[11] The Tudor Gothic quadrangle and early campus buildings were designed and built by Sir Thomas Deane (1792-1871) and Benjamin Woodward (1816-1861). Queen's College Cork officially opened its doors in November 1849, with further buildings added later, including the Medical/Windle Building in the 1860s.[12]

In the following century, the Irish Universities Act (1908) formed the National University of Ireland, consisting of the three constituent colleges of Dublin, Cork and Galway, and the college was given the status of a university college as University College, Cork. The Universities Act, 1997, made the university college a constituent university of the National University and made the constituent university a full university for all purposes except the awarding of degrees and diplomas which remains the sole remit of the National University.

As of 2016, University College Cork (UCC) had 21,000 students. These included 15,000 in undergraduate programmes, 4,400 in postgraduate study and research, and 2,800 in adult continuing education across undergraduate, postgraduate and short courses.[4] The student base is supported by 2,800 academic, research and administrative staff.[13] As of 2017, UCC reportedly had 150,000 alumni worldwide.[13]

Student numbers, at over 21,000 in 2016,[4] increased from the late 1980s, precipitating the expansion of the campus by the acquisition of adjacent buildings and lands. This expansion continued with the opening of the Alfred O'Rahilly building in the late 1990s, the Cavanagh Pharmacy building, the Brookfield Health Sciences centre, the extended Áras na MacLéinn (Devere Hall), the Lewis Glucksman Gallery in 2004, Experience UCC (Visitors' Centre) and an extension to the Boole Library – named for the first professor of mathematics at UCC, George Boole, who developed the algebra that would later make computer programming possible. The university also completed the Western Gateway Building in 2009 on the site of the former Cork Greyhound track on the Western Road as well as refurbishment to the Tyndall institute buildings at the Lee Maltings Complex. In 2016, UCC acquired the Cork Savings Bank building on Lapps Quay in the centre of Cork city.[4] As of 2017, the university is rolling out a programme to increase the space across its campuses, with part of this development involving the creation of a 'student hub' to support academic strategy, to add 600 new student accommodation spaces, and to develop an outdoor sports facility.[4]

The School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences is based on the North Mall Campus, the site of the former North Mall Distillery.

Since 1986, 2.5 tonnes of uranium rods have been stored in the basement of the UCC physics department. The uranium was originally given to Ireland by the US as part of the Atoms for Peace programme, however due to public opposition, the reactor was dismantled during the 1980s. As there is no nuclear waste site in Ireland, the uranium remains on campus.[14][15]

In 2006, the university re-opened the Crawford Observatory, a structure built in 1880 on the grounds of the university by Sir Howard Grubb. Grubb, son of the Grubb telescope building family in Dublin, designed the observatory and built the astronomical instruments for the structure. The university paid for an extensive restoration and conservation of the building and the three main telescopes, the Equatorial, the Transit Circle and Sidereostatic telescopes.[16]

In November 2009, a number of UCC buildings were damaged by flooding.[17] The floods also affected other parts of Cork City, with many students being evacuated from accommodation. The college authorities postponed academic activities for a week,[17] and indicated that it would take until 2010 before all flood damaged property would be repaired. Particularly impacted was the newly opened Western Gateway Building, with the main lecture theatre requiring a total refit just months after opening for classes.[18]

In 2018, UCC's campus became home to the first "plastic free" café in Ireland, with the opening of the Bio Green Café in the Biosciences building.[19]

The university is one of Ireland's leading research institutes, with among the highest research income in the state.[20] In 2016, UCC secured research funding of over €96 million, a 21% increase over a five-year period and a high for the university.[4] The university had seven faculties: Arts and Celtic Studies, Commerce, Engineering, Food Science and Technology, Law, Medicine, and Science. Between 2005 and 2006 the university was restructured from these seven faculties into four colleges: Arts, Celtic Studies and Social Science; Business and Law; Medicine and Health; and Science, Engineering and Food Science.[21][22][23]

According to the 2009-2012 UCC Strategic plan,[24] UCC aimed to enhance research and innovation. In 2009, the university was ranked in the top 3% of universities worldwide for research.[25]

UCC's published research strategy proposed to create "Centres of Excellence" for "world class research" in which the researchers and research teams would be given "freedom and flexibility to pursue their areas of research".[24] Research centres in UCC cover a range of areas including: Nanoelectronics with the Tyndall Institute; Food and Health with the Alimentary Pharmabiotic Centre,[26] NutraMara,[27] Food for Health Ireland Research Centre,[28] and Cereal Science Cork;[29] the Environment with the Environmental Research Institute[30] (with research in biodiversity, aquaculture, energy efficiency and ocean energy); and Business Information Systems.[31]

The Sunday Times "Good University Guide 2015", put UCC at the top of their rankings for "research income per academic".[32]

In October 2008, the governing body of the university announced that UCC would be the first institution in Ireland to use embryonic stem cells in research[33] under strict guidelines of the University Research Ethics using imported hESCs from approved jurisdictions.[34] In 2009, Professor of Mathematics at UCC, Des McHale, challenged the university's decision to allow embryonic stem cell research.[35] According to the results of a poll conducted by irishhealth.com, almost two in three people supported the decision made by University College Cork to allow embryonic stem cell research.[36]

In 2016, Professor Noel Caplice, director of the centre for research in Vascular Biology at UCC and a cardiologist at Cork University Hospital, announced a "major breakthrough in the field of blood vessel replacement".[37]

The university has a number of related companies including: Cytrea, which is involved in pharmaceutical formulations;[38] Firecomms, an ICT company concentrating on optical communications;[39] Alimentary Health a biotech healthcare company;[40] Biosensia who develop integrated micro-system analytical chips;[41] Sensl, part of ON Semiconductor; Luxcel which is involved in the development of probes and sensors;[42] and Optical Metrology Innovations which develops laser metrology systems.[43]

Innovation and Knowledge transfer is driven by UCC's Office of Technology Transfer,[44] an office of the university dedicated to commercialising aspects of UCC's research and connecting researchers with industry. Recent spin outs from the college include pharmaceutical company Glantreo,[45] Luxcel Biosciences,[46] Alimentary Health, Biosensia, Firecoms, Gourmet Marine, Keelvar, Lee Oncology, and Sensl.[47]

In 2015, the university marked the bicentenary of mathematician, philosopher and logician George Boole - UCC's first professor of mathematics.[48] In September 2017, UCC unveiled a €350 million investment plan, with university president, Professor Patrick O’Shea, outlining the development goals for UCC in the areas of philanthropy and student recruitment.[49] The plan proposes to provide for curriculum development, an increase in national and international student numbers, the extension of the campus and an increase in the income earned from philanthropy.[49]

The Minister for Culture, Heritage & the Gaeltacht and Chair of the National Famine Commemoration Committee, Heather Humphreys TD, also announced that 2018's National Famine Commemoration is planned to take place in UCC.[49][50] Cork University Press published The Atlas of the Great Irish Famine in 2012.[51] Subsequently, in September 2017, The Atlas of the Irish Revolution was published by Cork University Press.[51] In November 2017, UCC's MSc Information Systems for Business Performance (ISBP) was named "Postgraduate Course of the Year - IT" at the gradireland Higher Education Awards in Dublin.[52]

University College Cork has been ranked by a number of bodies, and was named as the "Irish University of the Year" by the Sunday Times in 2003, 2005, 2011 and 2016,[9] and was a runner up in the 2015 edition.[32] In 2015, UCC was also named as top performing university by the European Commission funded U-Multirank system, based on a high number of "A" scores (21 out of 28 metrics) among a field of 1200 partaking universities.[10] Also in 2015, the CWTS Leiden Ranking placed UCC 1st in Ireland, 16th in Europe and 52nd globally from a field of 750 universities.[53] The 2011 QS World University Rankings assigned a 5-star rating to UCC,[54] and ranked the university amongst the top 2% of universities worldwide. UCC was ranked 230th in the 2014 edition of the QS World University Rankings.[55] 13 of its subject areas featured in the QS World University Rankings by Subject 2015 (up from 10 subject areas in 2014), including the Pharmacy & Pharmacology disciplines, which were listed with the top 50 worldwide.[56] The Universitas Indonesia (UI) Greenmetric World University Ranking awarded UCC a second in the world ranking for the second year in a row in 2015 for its efforts in the area of sustainability, with 360 universities from 62 countries ranked overall.[57]

UCC has been recognised for its digital and social media presence, winning the 'Best Social Media Engagement' category at the 2014 Social Media Awards,[58] and as a finalist in two categories at the 2015 Social Media Awards.[58] A previous finalist at the 2013 and 2014 Web Awards, UCC also made the 2015 finals in two categories,[59] 'Most Influential Irish Website Ever' and 'Best Education and Third Level Website'. University College Cork had the first website in Ireland in 1991[59] (only the ninth website in the world at the time), serving transcriptions of Irish historical and literary documents for the CELT project converted from SGML to HTML.

It was reported in December 2020 that UCC had spent €76,265.38 investigating sexual harassment claims over the previous five years. This represented the largest amount spent by a third-level institution in Ireland during that period. UCC spent €24,460.50 on legal fees in the years 2017 and 2018, and paid out €510 in 2018.[60]

Medicine, Arts, and Law were the three founding faculties when Queen's College Cork opened its doors to students in 1849. The medical buildings were built in stages between 1860 and 1880, and the faculty quickly gained a reputation for the quality of its graduates. The first two women to graduate in medicine in Ireland did so in 1898 (this was notable as it was more than 20 years before women were permitted to sit for medicine at the University of Oxford).[61] UCC School of Medicine is part of the College of Medicine and Health, and is based at the Brookfield Health Sciences Centre on the main UCC campus and is affiliated with the 1000-bed University College Cork Teaching Hospital, which is the largest medical centre in Ireland. The UCC School Of Pharmacy is based in the Cavanagh Pharmacy Building.[61]

The Cork Centre for Architectural Education (CCAE) is the Department of Architecture at UCC, and is a school jointly run with Munster Technological University. It is accredited by the Royal Institute of the Architects of Ireland.[62][63]

The College of Arts, Celtic Studies and Social Sciences (CACSSS) incorporates a number of schools.[64]

UCC is home to the Irish Institute of Chinese Studies, which allows students to study Chinese culture as well as the language through Arts and Commerce. The department won the European Award for Languages in 2008.[65]

As of 2017, Digital Humanities had grown as a discipline, with 26 PhD research students working on various Digital Humanities projects.[66] UCC's programme for students in Digital Humanities includes BA (Hons) Digital Humanities & Information Technology, MA Digital Arts & Humanities and PhD Digital Arts & Humanities.[67]

University College Cork has over 100 active societies[68] and 50 different sports clubs.[69][70] There are academic, charitable, creative, gaming/role-playing, political, religious, and social societies and clubs incorporating field sports, martial arts, watersports as well outdoor and indoor team and individual sports. UCC clubs are sponsored by Bank of Ireland, with the UCC Skull and Crossbones as the mascot for all UCC sports teams. 100 students received scholarships in 26 different sports in 2010.[69]

The regular activities of UCC's societies include charity work; with over €100,000 raised annually by the Surgeon Noonan society, €10,000 raised by the War Gaming and Role Playing Society (WARPS) through its international gaming convention Warpcon, €10,000 raised by the UCC Law Society for the Cambodia orphanage and the UCC Pharmacy Society supports the Cork Hospitals Children's Club every year with a number of events.[71] UCC societies also sometimes attract high-profile speakers such as Robert Fisk who addressed the Law Society, Nick Leeson,[71] and Senator David Norris, who was the 2009/2010 honorary president of the UCC Philosophical Society.[72]

An Chuallacht (Irish pronunciation: [ənˠ ˈxuəl̪ˠaxt̪ˠ], meaning "The Fellowship") is UCC's Irish language and culture society. Founded in 1912, this society promotes the Irish language, and was awarded the Glór na nGael "Irish Society of the Year Award" in 2009.[73]

The UCC Students' Union (UCCSU) acts as the representative body of the 17,000 students attending UCC. Each student is automatically a member by virtue of a student levy.

Accommodation for students is offered by UCC through a subsidiary company known as Campus Accommodation UCC DAC.[74] UCC operate 5 accommodation complexes, including the Castlewhite Apartments (63 apartments/298 beds),[75] Mardyke Hall (14 apartments/48 beds),[76]

In February 2020, UCC announced their decision to raise rent in the 2020/21 academic term by three-percent over the 2019/20 academic term rate.[77] The announcement came after similar rent increases in university-owned accommodation throughout the country,[78] and after increases in previous years to the rent of UCC-owned accommodation.[79] This decision was met with backlash from student representatives, UCC staff, and local politicians. On 25 February 2020, the UCC Students' Union launched a campaign which demanded that UCC reverse the increase.[80][81] A group of over 300 UCC staff members signed a petition in solidarity with the Students' Union.[82] Several members of Cork County Council also expressed opposition to the decision.[83] In early March 2020, a spokesperson for the university said the increase was necessary due to refurbishment works, and a rise in security and maintenance costs.[84][85]

The largest number of the 2,400 international students at UCC in 2010 came from the United States, followed by China, France and Malaysia.[86] UCC participates in the Erasmus program with 439 students visiting UCC in 2009–2010.[86] 201 UCC students studied in institutions in the United States, China and Europe in the same period.[86]

UCC was rated highly in the 2008 International Student Barometer report.[87] This survey polled 67,000 international students studying at 84 institutions, and was carried out by the International Insight Group.[87] The report held that 98% of UCC's international students (who participated in the survey) reported having "Expert Lecturers". And over 90% of these students said that they had "Good Teachers".[87] In 3 categories of the survey, "sports facilities", "social facilities" and "university clubs and societies", UCC was in the top three of the 84 Institutions that took part in the survey. UCC's International Education Office was given a 93% satisfaction rating and UCC's IT Support was given a 92% satisfaction rating.[87]

Notable alumni of the university include graduates from different disciplines.

In arts and literature,[88] alumni include novelist Seán Ó Faoláin, short-story writer Daniel Corkery, composers Aloys Fleischmann, Seán Ó Riada, musicologist Ita Beausang, musician Julie Feeney, author, academic and critic Robert Anthony Welch, actors Fiona Shaw and Siobhán McSweeney, novelist and poet William Wall, poets Paul Durcan, John Mee,[89] Liam Ó Muirthile,[90] Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill, Trevor Joyce, Thomas McCarthy, Theo Dorgan,[91] and Greg Delanty, singer SEARLS, comedian Des Bishop,[92] and journalists Brendan O'Connor,[93] Ian Bailey,[94] Samantha Barry,[95] Stefanie Preissner[96] and Eoghan Harris.[97] Actor Cillian Murphy and BBC presenter Graham Norton both attended UCC but did not graduate.[98][99]

From the business community, alumni include Kerry Group's Denis Brosnan,[100] Kingfisher plc's former CEO Gerry Murphy,[100] former heads of CRH Anthony Barry and Myles Lee.[100][101]

In medicine, alumni include Sir Edwin John Butler, Charles Donovan, Sir Bertram Windle, Dr. Paul Whelton, and Dr. Pixie McKenna, doctor and TV presenter.[102]

In physics, alumni include Professor Margaret Murnane of the University of Colorado, Professor Patrick G. O'Shea of the University of Maryland, and Professor Séamus Davis of Cornell.[103]

In mathematics alumni include Irish mathematicians Seán Dineen, an expert in complex analysis, and Des MacHale, a leading researcher on George Boole,.[104]

Politicians and public servants that attended UCC include current Taoiseach Micheál Martin, former Taoiseach Jack Lynch,[105] Supreme Court justice Liam McKechnie, High Court judge Bryan MacMahon.[106] André Ventura, founder of the Portuguese political party Chega, attended UCC as a graduate student.[107]

In religious communities alumni have included the Church of Ireland Bishop of Cork, Cloyne and Ross, Dr Paul Colton, the first UCC graduate to be a Church of Ireland bishop.[108] Some members of the Saint Patrick's Society for the Foreign Missions (Kiltegan Fathers) took their civil degrees in UCC, including Derek John Christopher Byrne, Catholic Bishop in Brazil, Maurice Anthony Crowley SPS in Kenya, John Alphonsus Ryan Bishop in Malawi, and John Magee who served as Bishop of Cloyne.[citation needed] Bishop of Kerry, Raymond Browne, holds a science degree from UCC.[citation needed]

In sport, rugby coach Declan Kidney,[109] Gaelic footballers Séamus Moynihan, Maurice Fitzgerald and Billy Morgan, hurlers Pat Heffernan, Joe Deane, James "Cha" Fitzpatrick and Ray Cummins, rugby players Moss Keane, Ronan O'Gara and Donnacha Ryan, and Olympian Lizzie Lee have all attended UCC.[110]

|

Cork

Corcaigh

|

|

|---|---|

|

City

|

|

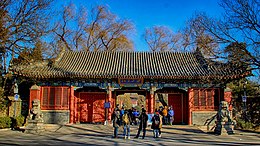

From top, left to right: City Hall, the English Market, Quadrangle in UCC, the River Lee, Shandon Steeple

|

|

| Nicknames:

The Rebel City, Leeside, The Real Capital

|

|

| Motto(s): | |

|

|

Coordinates:  51°53′50″N 8°28′12″WCoordinates: 51°53′50″N 8°28′12″WCoordinates:  51°53′50″N 8°28′12″W 51°53′50″N 8°28′12″W |

|

| State | Ireland |

| Province | Munster |

| Region | Southern |

| County | Cork |

| Founded | 6th century AD |

| City rights | 1185 AD |

| Government | |

| • Type | Cork City Council |

| • Lord Mayor | Deirdre Forde (FG) |

| • Local electoral areas |

|

| • Dáil constituency | |

| • European Parliament | South |

| Area | |

| • City | 187 km2 (72 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 174 km2 (67 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 820 km2 (320 sq mi) |

| Population

(2022)

|

|

| • City | 222,333[3] |

| • Density | 1,188/km2 (3,080/sq mi) |

| • Metro

(2017)

|

305,222[5] |

| • Demonym | Corkonian or Leesider |

| Time zone | UTC0 (WET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (IST) |

| Eircode |

T12 and T23

|

| Area code | 021 |

| Vehicle index mark code |

C |

| Website | www.corkcity.ie |

A university (from Latin universitas 'a whole') is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. Universities typically offer both undergraduate and postgraduate programs.

The word university is derived from the Latin universitas magistrorum et scholarium, which roughly means "community of teachers and scholars".[1]

The first universities were created in Europe by Catholic Church monks.[2][3][4][5][6] The University of Bologna (Università di Bologna), founded in 1088, is the first university in the sense of:

The original Latin word universitas refers in general to "a number of persons associated into one body, a society, company, community, guild, corporation, etc".[12] At the time of the emergence of urban town life and medieval guilds, specialized "associations of students and teachers with collective legal rights usually guaranteed by charters issued by princes, prelates, or the towns in which they were located" came to be denominated by this general term. Like other guilds, they were self-regulating and determined the qualifications of their members.[13]

In modern usage the word has come to mean "An institution of higher education offering tuition in mainly non-vocational subjects and typically having the power to confer degrees,"[14] with the earlier emphasis on its corporate organization considered as applying historically to Medieval universities.[15]

The original Latin word referred to degree-awarding institutions of learning in Western and Central Europe, where this form of legal organisation was prevalent and from where the institution spread around the world.[citation needed]

An important idea in the definition of a university is the notion of academic freedom. The first documentary evidence of this comes from early in the life of the University of Bologna, which adopted an academic charter, the Constitutio Habita,[16] in 1158 or 1155,[17] which guaranteed the right of a traveling scholar to unhindered passage in the interests of education. Today this is claimed as the origin of "academic freedom".[18] This is now widely recognised internationally – on 18 September 1988, 430 university rectors signed the Magna Charta Universitatum,[19] marking the 900th anniversary of Bologna's foundation. The number of universities signing the Magna Charta Universitatum continues to grow, drawing from all parts of the world.

Scholars occasionally call the University of al-Qarawiyyin (name given in 1963), founded as a mosque by Fatima al-Fihri in 859, a university,[21][22][23][24] although Jacques Verger writes that this is done out of scholarly convenience.[25] Several scholars consider that al-Qarawiyyin was founded[26][27] and run[20][28][29][30][31] as a madrasa until after World War II. They date the transformation of the madrasa of al-Qarawiyyin into a university to its modern reorganization in 1963.[32][33][20] In the wake of these reforms, al-Qarawiyyin was officially renamed "University of Al Quaraouiyine" two years later.[32]

Some scholars, including George Makdisi, have argued that early medieval universities were influenced by the madrasas in Al-Andalus, the Emirate of Sicily, and the Middle East during the Crusades.[34][35][36] Norman Daniel, however, views this argument as overstated.[37] Roy Lowe and Yoshihito Yasuhara have recently drawn on the well-documented influences of scholarship from the Islamic world on the universities of Western Europe to call for a reconsideration of the development of higher education, turning away from a concern with local institutional structures to a broader consideration within a global context.[38]

The modern university is generally regarded as a formal institution that has its origin in the Medieval Christian tradition.[39][40]

European higher education took place for hundreds of years in cathedral schools or monastic schools (scholae monasticae), in which monks and nuns taught classes; evidence of these immediate forerunners of the later university at many places dates back to the 6th century.[41]

In Europe, young men proceeded to university when they had completed their study of the trivium – the preparatory arts of grammar, rhetoric and dialectic or logic–and the quadrivium: arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy.

The earliest universities were developed under the aegis of the Latin Church by papal bull as studia generalia and perhaps from cathedral schools. It is possible, however, that the development of cathedral schools into universities was quite rare, with the University of Paris being an exception.[42] Later they were also founded by kings (University of Naples Federico II, Charles University in Prague, Jagiellonian University in Kraków) or municipal administrations (University of Cologne, University of Erfurt). In the early medieval period, most new universities were founded from pre-existing schools, usually when these schools were deemed to have become primarily sites of higher education. Many historians state that universities and cathedral schools were a continuation of the interest in learning promoted by The residence of a religious community.[43] Pope Gregory VII was critical in promoting and regulating the concept of modern university as his 1079 Papal Decree ordered the regulated establishment of cathedral schools that transformed themselves into the first European universities.[44]

The first universities in Europe with a form of corporate/guild structure were the University of Bologna (1088), the University of Paris (c.1150, later associated with the Sorbonne), and the University of Oxford (1167).

The University of Bologna began as a law school teaching the ius gentium or Roman law of peoples which was in demand across Europe for those defending the right of incipient nations against empire and church. Bologna's special claim to Alma Mater Studiorum[clarification needed] is based on its autonomy, its awarding of degrees, and other structural arrangements, making it the oldest continuously operating institution[17] independent of kings, emperors or any kind of direct religious authority.[45][46]

The conventional date of 1088, or 1087 according to some,[47] records when Irnerius commences teaching Emperor Justinian's 6th-century codification of Roman law, the Corpus Iuris Civilis, recently discovered at Pisa. Lay students arrived in the city from many lands entering into a contract to gain this knowledge, organising themselves into 'Nationes', divided between that of the Cismontanes and that of the Ultramontanes. The students "had all the power … and dominated the masters".[48][49]

All over Europe rulers and city governments began to create universities to satisfy a European thirst for knowledge, and the belief that society would benefit from the scholarly expertise generated from these institutions. Princes and leaders of city governments perceived the potential benefits of having a scholarly expertise develop with the ability to address difficult problems and achieve desired ends. The emergence of humanism was essential to this understanding of the possible utility of universities as well as the revival of interest in knowledge gained from ancient Greek texts.[50]

The recovery of Aristotle's works – more than 3000 pages of it would eventually be translated – fuelled a spirit of inquiry into natural processes that had already begun to emerge in the 12th century. Some scholars believe that these works represented one of the most important document discoveries in Western intellectual history.[51] Richard Dales, for instance, calls the discovery of Aristotle's works "a turning point in the history of Western thought."[52] After Aristotle re-emerged, a community of scholars, primarily communicating in Latin, accelerated the process and practice of attempting to reconcile the thoughts of Greek antiquity, and especially ideas related to understanding the natural world, with those of the church. The efforts of this "scholasticism" were focused on applying Aristotelian logic and thoughts about natural processes to biblical passages and attempting to prove the viability of those passages through reason. This became the primary mission of lecturers, and the expectation of students.

The university culture developed differently in northern Europe than it did in the south, although the northern (primarily Germany, France and Great Britain) and southern universities (primarily Italy) did have many elements in common. Latin was the language of the university, used for all texts, lectures, disputations and examinations. Professors lectured on the books of Aristotle for logic, natural philosophy, and metaphysics; while Hippocrates, Galen, and Avicenna were used for medicine. Outside of these commonalities, great differences separated north and south, primarily in subject matter. Italian universities focused on law and medicine, while the northern universities focused on the arts and theology. There were distinct differences in the quality of instruction in these areas which were congruent with their focus, so scholars would travel north or south based on their interests and means. There was also a difference in the types of degrees awarded at these universities. English, French and German universities usually awarded bachelor's degrees, with the exception of degrees in theology, for which the doctorate was more common. Italian universities awarded primarily doctorates. The distinction can be attributed to the intent of the degree holder after graduation – in the north the focus tended to be on acquiring teaching positions, while in the south students often went on to professional positions.[53] The structure of northern universities tended to be modeled after the system of faculty governance developed at the University of Paris. Southern universities tended to be patterned after the student-controlled model begun at the University of Bologna.[54] Among the southern universities, a further distinction has been noted between those of northern Italy, which followed the pattern of Bologna as a "self-regulating, independent corporation of scholars" and those of southern Italy and Iberia, which were "founded by royal and imperial charter to serve the needs of government."[55]

During the Early Modern period (approximately late 15th century to 1800), the universities of Europe would see a tremendous amount of growth, productivity and innovative research. At the end of the Middle Ages, about 400 years after the first European university was founded, there were 29 universities spread throughout Europe. In the 15th century, 28 new ones were created, with another 18 added between 1500 and 1625.[58] This pace continued until by the end of the 18th century there were approximately 143 universities in Europe, with the highest concentrations in the German Empire (34), Italian countries (26), France (25), and Spain (23) – this was close to a 500% increase over the number of universities toward the end of the Middle Ages. This number does not include the numerous universities that disappeared, or institutions that merged with other universities during this time.[59] The identification of a university was not necessarily obvious during the Early Modern period, as the term is applied to a burgeoning number of institutions. In fact, the term "university" was not always used to designate a higher education institution. In Mediterranean countries, the term studium generale was still often used, while "Academy" was common in Northern European countries.[60]

The propagation of universities was not necessarily a steady progression, as the 17th century was rife with events that adversely affected university expansion. Many wars, and especially the Thirty Years' War, disrupted the university landscape throughout Europe at different times. War, plague, famine, regicide, and changes in religious power and structure often adversely affected the societies that provided support for universities. Internal strife within the universities themselves, such as student brawling and absentee professors, acted to destabilize these institutions as well. Universities were also reluctant to give up older curricula, and the continued reliance on the works of Aristotle defied contemporary advancements in science and the arts.[61] This era was also affected by the rise of the nation-state. As universities increasingly came under state control, or formed under the auspices of the state, the faculty governance model (begun by the University of Paris) became more and more prominent. Although the older student-controlled universities still existed, they slowly started to move toward this structural organization. Control of universities still tended to be independent, although university leadership was increasingly appointed by the state.[62]

Although the structural model provided by the University of Paris, where student members are controlled by faculty "masters", provided a standard for universities, the application of this model took at least three different forms. There were universities that had a system of faculties whose teaching addressed a very specific curriculum; this model tended to train specialists. There was a collegiate or tutorial model based on the system at University of Oxford where teaching and organization was decentralized and knowledge was more of a generalist nature. There were also universities that combined these models, using the collegiate model but having a centralized organization.[63]

Early Modern universities initially continued the curriculum and research of the Middle Ages: natural philosophy, logic, medicine, theology, mathematics, astronomy, astrology, law, grammar and rhetoric. Aristotle was prevalent throughout the curriculum, while medicine also depended on Galen and Arabic scholarship. The importance of humanism for changing this state-of-affairs cannot be underestimated.[64] Once humanist professors joined the university faculty, they began to transform the study of grammar and rhetoric through the studia humanitatis. Humanist professors focused on the ability of students to write and speak with distinction, to translate and interpret classical texts, and to live honorable lives.[65] Other scholars within the university were affected by the humanist approaches to learning and their linguistic expertise in relation to ancient texts, as well as the ideology that advocated the ultimate importance of those texts.[66] Professors of medicine such as Niccolò Leoniceno, Thomas Linacre and William Cop were often trained in and taught from a humanist perspective as well as translated important ancient medical texts. The critical mindset imparted by humanism was imperative for changes in universities and scholarship. For instance, Andreas Vesalius was educated in a humanist fashion before producing a translation of Galen, whose ideas he verified through his own dissections. In law, Andreas Alciatus infused the Corpus Juris with a humanist perspective, while Jacques Cujas humanist writings were paramount to his reputation as a jurist. Philipp Melanchthon cited the works of Erasmus as a highly influential guide for connecting theology back to original texts, which was important for the reform at Protestant universities.[67] Galileo Galilei, who taught at the Universities of Pisa and Padua, and Martin Luther, who taught at the University of Wittenberg (as did Melanchthon), also had humanist training. The task of the humanists was to slowly permeate the university; to increase the humanist presence in professorships and chairs, syllabi and textbooks so that published works would demonstrate the humanistic ideal of science and scholarship.[68]

Although the initial focus of the humanist scholars in the university was the discovery, exposition and insertion of ancient texts and languages into the university, and the ideas of those texts into society generally, their influence was ultimately quite progressive. The emergence of classical texts brought new ideas and led to a more creative university climate (as the notable list of scholars above attests to). A focus on knowledge coming from self, from the human, has a direct implication for new forms of scholarship and instruction, and was the foundation for what is commonly known as the humanities. This disposition toward knowledge manifested in not simply the translation and propagation of ancient texts, but also their adaptation and expansion. For instance, Vesalius was imperative for advocating the use of Galen, but he also invigorated this text with experimentation, disagreements and further research.[69] The propagation of these texts, especially within the universities, was greatly aided by the emergence of the printing press and the beginning of the use of the vernacular, which allowed for the printing of relatively large texts at reasonable prices.[70]

Examining the influence of humanism on scholars in medicine, mathematics, astronomy and physics may suggest that humanism and universities were a strong impetus for the scientific revolution. Although the connection between humanism and the scientific discovery may very well have begun within the confines of the university, the connection has been commonly perceived as having been severed by the changing nature of science during the Scientific Revolution. Historians such as Richard S. Westfall have argued that the overt traditionalism of universities inhibited attempts to re-conceptualize nature and knowledge and caused an indelible tension between universities and scientists.[71] This resistance to changes in science may have been a significant factor in driving many scientists away from the university and toward private benefactors, usually in princely courts, and associations with newly forming scientific societies.[72]

Other historians find incongruity in the proposition that the very place where the vast number of the scholars that influenced the scientific revolution received their education should also be the place that inhibits their research and the advancement of science. In fact, more than 80% of the European scientists between 1450 and 1650 included in the Dictionary of Scientific Biography were university trained, of which approximately 45% held university posts.[73] It was the case that the academic foundations remaining from the Middle Ages were stable, and they did provide for an environment that fostered considerable growth and development. There was considerable reluctance on the part of universities to relinquish the symmetry and comprehensiveness provided by the Aristotelian system, which was effective as a coherent system for understanding and interpreting the world. However, university professors still utilized some autonomy, at least in the sciences, to choose epistemological foundations and methods. For instance, Melanchthon and his disciples at University of Wittenberg were instrumental for integrating Copernican mathematical constructs into astronomical debate and instruction.[74] Another example was the short-lived but fairly rapid adoption of Cartesian epistemology and methodology in European universities, and the debates surrounding that adoption, which led to more mechanistic approaches to scientific problems as well as demonstrated an openness to change. There are many examples which belie the commonly perceived intransigence of universities.[75] Although universities may have been slow to accept new sciences and methodologies as they emerged, when they did accept new ideas it helped to convey legitimacy and respectability, and supported the scientific changes through providing a stable environment for instruction and material resources.[76]

Regardless of the way the tension between universities, individual scientists, and the scientific revolution itself is perceived, there was a discernible impact on the way that university education was constructed. Aristotelian epistemology provided a coherent framework not simply for knowledge and knowledge construction, but also for the training of scholars within the higher education setting. The creation of new scientific constructs during the scientific revolution, and the epistemological challenges that were inherent within this creation, initiated the idea of both the autonomy of science and the hierarchy of the disciplines. Instead of entering higher education to become a "general scholar" immersed in becoming proficient in the entire curriculum, there emerged a type of scholar that put science first and viewed it as a vocation in itself. The divergence between those focused on science and those still entrenched in the idea of a general scholar exacerbated the epistemological tensions that were already beginning to emerge.[77]

The epistemological tensions between scientists and universities were also heightened by the economic realities of research during this time, as individual scientists, associations and universities were vying for limited resources. There was also competition from the formation of new colleges funded by private benefactors and designed to provide free education to the public, or established by local governments to provide a knowledge-hungry populace with an alternative to traditional universities.[78] Even when universities supported new scientific endeavors, and the university provided foundational training and authority for the research and conclusions, they could not compete with the resources available through private benefactors.[79]

By the end of the early modern period, the structure and orientation of higher education had changed in ways that are eminently recognizable for the modern context. Aristotle was no longer a force providing the epistemological and methodological focus for universities and a more mechanistic orientation was emerging. The hierarchical place of theological knowledge had for the most part been displaced and the humanities had become a fixture, and a new openness was beginning to take hold in the construction and dissemination of knowledge that were to become imperative for the formation of the modern state.

Modern universities constitute a guild or quasi-guild system. This facet of the university system did not change due to its peripheral standing in an industrialized economy; as commerce developed between towns in Europe during the Middle Ages, though other guilds stood in the way of developing commerce and therefore were eventually abolished, the scholars guild did not. According to historian Elliot Krause, "The university and scholars' guilds held onto their power over membership, training, and workplace because early capitalism was not interested in it."[80]

By the 18th century, universities published their own research journals and by the 19th century, the German and the French university models had arisen. The German, or Humboldtian model, was conceived by Wilhelm von Humboldt and based on Friedrich Schleiermacher's liberal ideas pertaining to the importance of freedom, seminars, and laboratories in universities.[citation needed] The French university model involved strict discipline and control over every aspect of the university.

Until the 19th century, religion played a significant role in university curriculum; however, the role of religion in research universities decreased during that century. By the end of the 19th century, the German university model had spread around the world. Universities concentrated on science in the 19th and 20th centuries and became increasingly accessible to the masses. In the United States, the Johns Hopkins University was the first to adopt the (German) research university model and pioneered the adoption of that model by most American universities. When Johns Hopkins was founded in 1876, "nearly the entire faculty had studied in Germany."[81] In Britain, the move from Industrial Revolution to modernity saw the arrival of new civic universities with an emphasis on science and engineering, a movement initiated in 1960 by Sir Keith Murray (chairman of the University Grants Committee) and Sir Samuel Curran, with the formation of the University of Strathclyde.[82] The British also established universities worldwide, and higher education became available to the masses not only in Europe.

In 1963, the Robbins Report on universities in the United Kingdom concluded that such institutions should have four main "objectives essential to any properly balanced system: instruction in skills; the promotion of the general powers of the mind so as to produce not mere specialists but rather cultivated men and women; to maintain research in balance with teaching, since teaching should not be separated from the advancement of learning and the search for truth; and to transmit a common culture and common standards of citizenship."[83]

In the early 21st century, concerns were raised over the increasing managerialisation and standardisation of universities worldwide. Neo-liberal management models have in this sense been critiqued for creating "corporate universities (where) power is transferred from faculty to managers, economic justifications dominate, and the familiar 'bottom line' eclipses pedagogical or intellectual concerns".[84] Academics' understanding of time, pedagogical pleasure, vocation, and collegiality have been cited as possible ways of alleviating such problems.[85]

A national university is generally a university created or run by a national state but at the same time represents a state autonomic institution which functions as a completely independent body inside of the same state. Some national universities are closely associated with national cultural, religious or political aspirations, for instance the National University of Ireland, which formed partly from the Catholic University of Ireland which was created almost immediately and specifically in answer to the non-denominational universities which had been set up in Ireland in 1850. In the years leading up to the Easter Rising, and in no small part a result of the Gaelic Romantic revivalists, the NUI collected a large amount of information on the Irish language and Irish culture.[citation needed] Reforms in Argentina were the result of the University Revolution of 1918 and its posterior reforms by incorporating values that sought for a more equal and laic[further explanation needed] higher education system.

Universities created by bilateral or multilateral treaties between states are intergovernmental. An example is the Academy of European Law, which offers training in European law to lawyers, judges, barristers, solicitors, in-house counsel and academics. EUCLID (Pôle Universitaire Euclide, Euclid University) is chartered as a university and umbrella organization dedicated to sustainable development in signatory countries, and the United Nations University engages in efforts to resolve the pressing global problems that are of concern to the United Nations, its peoples and member states. The European University Institute, a post-graduate university specialized in the social sciences, is officially an intergovernmental organization, set up by the member states of the European Union.

Although each institution is organized differently, nearly all universities have a board of trustees; a president, chancellor, or rector; at least one vice president, vice-chancellor, or vice-rector; and deans of various divisions. Universities are generally divided into a number of academic departments, schools or faculties. Public university systems are ruled over by government-run higher education boards[citation needed]. They review financial requests and budget proposals and then allocate funds for each university in the system. They also approve new programs of instruction and cancel or make changes in existing programs. In addition, they plan for the further coordinated growth and development of the various institutions of higher education in the state or country. However, many public universities in the world have a considerable degree of financial, research and pedagogical autonomy. Private universities are privately funded and generally have broader independence from state policies. However, they may have less independence from business corporations depending on the source of their finances.

The funding and organization of universities varies widely between different countries around the world. In some countries universities are predominantly funded by the state, while in others funding may come from donors or from fees which students attending the university must pay. In some countries the vast majority of students attend university in their local town, while in other countries universities attract students from all over the world, and may provide university accommodation for their students.[86]

The definition of a university varies widely, even within some countries. Where there is clarification, it is usually set by a government agency. For example:

In Australia, the Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency (TEQSA) is Australia's independent national regulator of the higher education sector. Students rights within university are also protected by the Education Services for Overseas Students Act (ESOS).

In the United States there is no nationally standardized definition for the term university, although the term has traditionally been used to designate research institutions and was once reserved for doctorate-granting research institutions. Some states, such as Massachusetts, will only grant a school "university status" if it grants at least two doctoral degrees.[87]

In the United Kingdom, the Privy Council is responsible for approving the use of the word university in the name of an institution, under the terms of the Further and Higher Education Act 1992.[88]

In India, a new designation deemed universities has been created for institutions of higher education that are not universities, but work at a very high standard in a specific area of study ("An Institution of Higher Education, other than universities, working at a very high standard in specific area of study, can be declared by the Central Government on the advice of the University Grants Commission as an Institution 'Deemed-to-be-university'"). Institutions that are 'deemed-to-be-university' enjoy the academic status and the privileges of a university.[89] Through this provision many schools that are commercial in nature and have been established just to exploit the demand for higher education have sprung up.[90]

In Canada, college generally refers to a two-year, non-degree-granting institution, while university connotes a four-year, degree-granting institution. Universities may be sub-classified (as in the Macleans rankings) into large research universities with many PhD-granting programs and medical schools (for example, McGill University); "comprehensive" universities that have some PhDs but are not geared toward research (such as Waterloo); and smaller, primarily undergraduate universities (such as St. Francis Xavier).

In Germany, universities are institutions of higher education which have the power to confer bachelor, master and PhD degrees. They are explicitly recognised as such by law and cannot be founded without government approval. The term Universität (i.e. the German term for university) is protected by law and any use without official approval is a criminal offense. Most of them are public institutions, though a few private universities exist. Such universities are always research universities. Apart from these universities, Germany has other institutions of higher education (Hochschule, Fachhochschule). Fachhochschule means a higher education institution which is similar to the former polytechnics in the British education system, the English term used for these German institutions is usually 'university of applied sciences'. They can confer master's degrees but no PhDs. They are similar to the model of teaching universities with less research and the research undertaken being highly practical. Hochschule can refer to various kinds of institutions, often specialised in a certain field (e.g. music, fine arts, business). They might or might not have the power to award PhD degrees, depending on the respective government legislation. If they award PhD degrees, their rank is considered equivalent to that of universities proper (Universität), if not, their rank is equivalent to universities of applied sciences.

Colloquially, the term university may be used to describe a phase in one's life: "When I was at university..." (in the United States and Ireland, college is often used instead: "When I was in college..."). In Ireland, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, the United Kingdom, Nigeria, the Netherlands, Italy, Spain and the German-speaking countries, university is often contracted to uni. In Ghana, New Zealand, Bangladesh and in South Africa it is sometimes called "varsity" (although this has become uncommon in New Zealand in recent years). "Varsity" was also common usage in the UK in the 19th century.[citation needed]

In many countries, students are required to pay tuition fees. Many students look to get 'student grants' to cover the cost of university. In 2016, the average outstanding student loan balance per borrower in the United States was US$30,000.[91] In many U.S. states, costs are anticipated to rise for students as a result of decreased state funding given to public universities.[92] Many universities in the United States offer students the opportunity to apply for financial scholarships to help pay for tuition based on academic achievement.

There are several major exceptions on tuition fees. In many European countries, it is possible to study without tuition fees. Public universities in Nordic countries were entirely without tuition fees until around 2005. Denmark, Sweden and Finland then moved to put in place tuition fees for foreign students. Citizens of EU and EEA member states and citizens from Switzerland remain exempted from tuition fees, and the amounts of public grants granted to promising foreign students were increased to offset some of the impact.[93] The situation in Germany is similar; public universities usually do not charge tuition fees apart from a small administrative fee. For degrees of a postgraduate professional level sometimes tuition fees are levied. Private universities, however, almost always charge tuition fees.

University College Cork Reviews

Munster Technological University Reviews

Dept. of Archaeology, University College Cork Reviews

School of Mathematical Sciences, University College Cork, Cork, Ireland Reviews

Cork College of FET - Morrison's Island Campus Reviews

Department of Music, University College Cork Reviews